I've been engaged in a battle to renew my business insurance lately. It's gone on for an unbelievably long time, because I can't find anyone to insure us properly.

When asked about the reasons why companies are - I'm going to say 'scared' - to insure my business, it seems to boil down to two things.

1) The majority of my work over the last ten years or so is for North American clients. This seems to terrify them.

2) The insurers seem hell bent on protecting the mythically vulnerable from me - rather than the other way round, in a system that protects other people from being copied by me.

As most illustrators will know, we are most at risk from being ripped off by a third party - including large companies and startlingly high-profile corporations who ought to know better (we all know who I'm talking about, insert your own anecdote here) than we are at risk of plotting to rip them off, or each other.

Dear Insurance Company Person,Thank you for forwarding the documents for the policy you propose for my business, after speaking with me on the phone for forty minutes yesterday. I'm unable to accept it, because it does not cover my needs.What’s quite bewildering at the moment is that, after almost 30 years in this trade - and I mean, wholeheartedly, professionally immersed in nothing but this trade, on a worldwide scale - I’m finding an increasing reluctance to insure me and my business. For over 20 of those years I’ve worked with American and Canadian clients, and clients elsewhere in the world, and historically it’s never been ‘a problem’ nor subject to any additional questioning or clauses.Over the last 4-5 years I’ve seen a creeping nervousness around that, and I do not see a reason why this would be. I don’t know of a single case of an illustrator being sued - for any reason - other than by another illustrator in cases of blatant copying. This happens - there was a case a few years ago of two American illustrators fighting it out over alleged copying, but it was eventually resolved without resort to legal means, which remains the preferred way of resolving such things.What I don’t see reflected in your policy, but do see happening around me frequently, is cases of the illustrator having to fight a case of having their own work infringed by companies - both small and large.To cite one example, a couple of years ago the large high street chain **redacted but named in the email** copied a colleague’s very distinctive work; that colleague had to fight that case of (very blatant) copying, and that colleague 'dealt with it satisfactorily' and got the work withdrawn. It was 'cut and dried’.There are myriad examples of large clothing companies helping themselves to artists’ work online, without permission.I myself have had to deal with over 60 copyright infringements of my work by other people to date - and I have dealt with them, successfully, without ever having to resort to legal means, because I know the business inside out and I know copyright - as it applies to my trade - inside out.The only recent example I know of which speaks to the kind of scenario that form the basis of this particular fear from insurance companies, is this. A very, very well-known British high street chain hired a design agency (standard practice) for a campaign that involved an illustrator creating a ‘friendly monster’ for a Christmas campaign. They would have briefed the illustrator closely for such a high profile campaign, and the resulting monster, once it hit the internet, was immediately recognised as a close copy of a long-existing famous character illustrated by an equally famous illustrator.The illustrator whose work had been copied, although within his rights to pursue the case, was maturely philosophical, resolving the issue with humour and grace:

"Talk of legal action has flooded my Facebook feeds, but I won’t be pursuing that. Instead, I hope that advertising agencies and the big companies they work for, take care to credit creative people whose work they might reference. We have the finest children’s book writers and illustrators in the world – their work should be cherished and credited properly."

The key issue though is even if legal action had been taken, it would have been the design agency hired by the company who was challenged, NOT the illustrator, as the design agency was responsible for the creative direction taken.(In this case the illustrator, who was relatively inexperienced and no doubt very excited to have received the commission, was unlikely to have questioned their commissioner’s art direction.)

But if that illustrator had chosen to pursue a legal route (and presuming he has insured his business) he should surely have been able to do that with the backing and confidence of his insurers, to whom he had paid money to protect that business, the IP in which forms the substance of the business in a far more meaningful way than his easily-replaced pens and pencils.

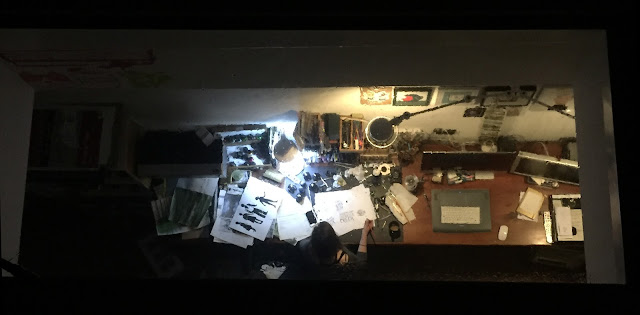

Such cases are not common. But my point is that what I am way, way more at risk of having MY copyright infringed, than I am at risk of infringing someone else’s - my job is to create original images, and I have created thousands of them.

The other scenario an insurer might be fearful of, and one that has been posited to me many times now, is an illustrator delivering work late, and thus triggering a sequence of damaging events such as missed print deadlines. But I have never heard of this happening; when deadlines are running close, they are modified, or the work is adapted to suit the timescale, or, in some cases, a client can choose to go with an other artist or buy stock imagery to meet their deadline - there is always a way forward, and I know because I have been involved in some extremely high profile jobs with their attendant deadlines, budgets and pressures, and successfully carried out every one of them.I’m not suggesting that legal challenges never come up, but the emphasis on a client suing an illustrator suggests a fundamental lack of understanding of the job of an illustrator and the industry at large. And this fear of legal challenges seems to be infiltrating the insurance industry, even those pitching themselves as specialists to the creative industries.I can’t go with your policy as it’s not right for me, but I welcome the opportunity to highlight why that is, and why the thinking underpinning the policy feels flawed, and outdated.All the best,Sarah.