After I’d been on BBC Leicester to talk about AI, I arranged to visit Andrea Soltoggio, Associate Professor in Artificial Intelligence at Loughborough University.

Although I probably knew a fair bit about AI compared to Maureen, busy shopping in the High Street when she was vox-popped by the Beeb (although not necessarily: Mo could be knocking out thousands of Made-By-MJ Adonises every night after work Because She Can Now) I realised I needed to increase my knowledge all-round; especially in the area of copyright, a wiring-loom-style nightmare of confusion that’s currently the subject of myriad studies and manifestos.

Andreja had been on the radio just before me, so I went over to the university and talked for an hour and a half over decent coffee.

I’ve advised on copyright and IP, and obviously deal with it regularly for work, but what I knew about AI and copyright amounted to this:

- First, copyright is automatic at the point of creation — in this country (the UK, from where I’m typing) you don’t have to ‘do’ anything ‘to copyright’ an artistic, photographic or literary creation.

- Copyright is enshrined in UK law, poignantly enough, as a human right by the Berne Convention of 1887, still applicable in law, which states:

- “All (artistic and literary works) except photographic and cinematographic which have different terms) shall be protected for at least 50 years after the author’s death, but parties are free to provide longer terms if they choose.”

- However there are many countries who are not signatories to the Berne Convention.

- The Copyright Act states that the author of an original work owns the copyright to that work. At the time the law was enacted, the purpose of copyright was to act as a financial and intellectual stimulus:

“The Act exists to incentivise original authentic effort. The person’s contribution is protected.” - This government page is a nicely readable, brief guide to whether and how your copyright is protected abroad, but since geography is irrelevent to AI-generated art, this is only so comforting.

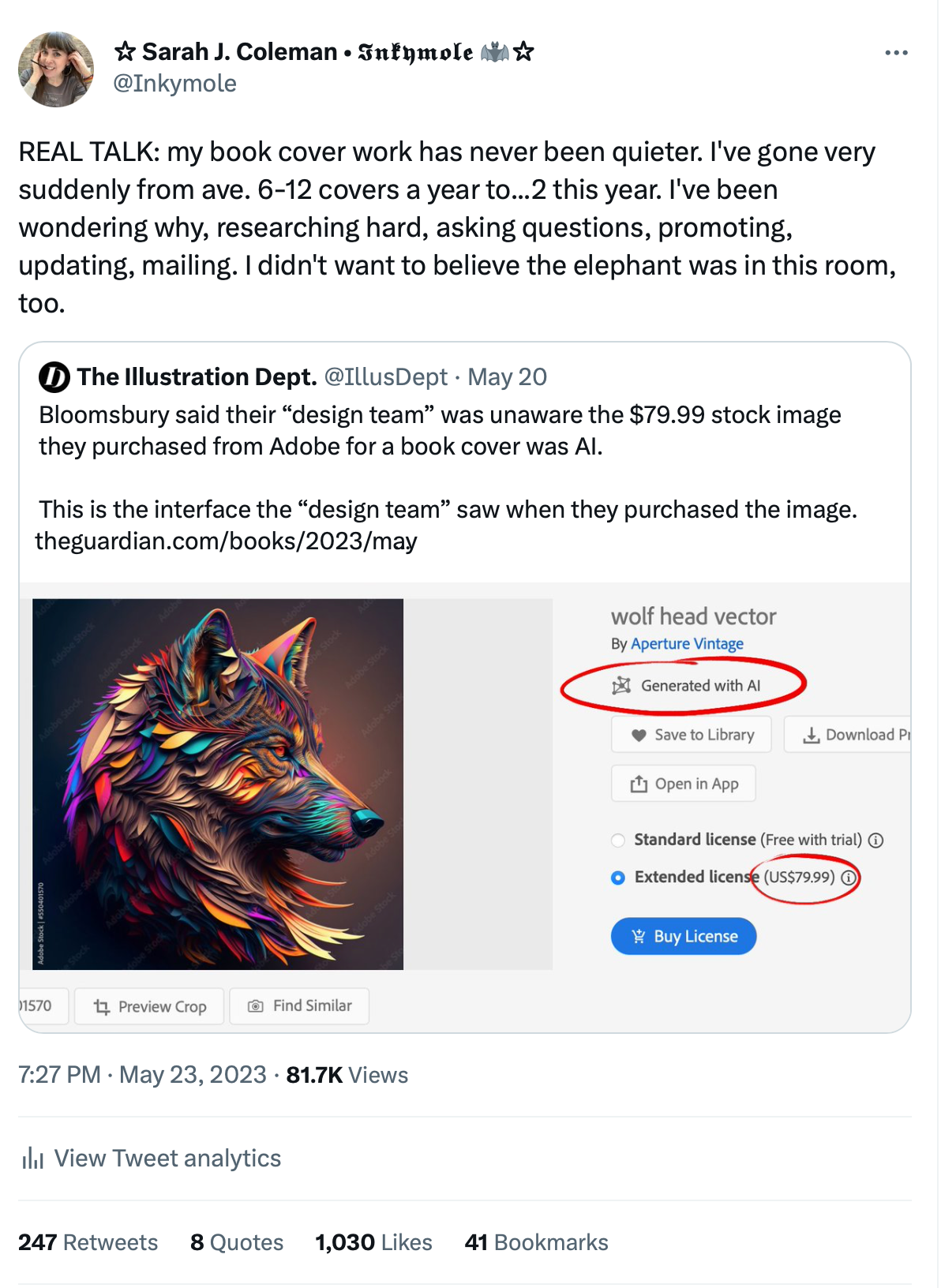

One of the largest swells of research and discussion has been to work out whether copyright can be claimed by someone making a picture using AI , and conversely, whether the copyright of an artist whose image has been ‘scraped’ from the www has been breached, which would normally automatically trigger a conversation about financial remuneration. This might seem obvious now, but it wasn’t at the creeping outset of the current rabid AI use, when it was all ‘look, I put my face into the Lensa app’ — you could never own those beautiful, flattering but heavily stylised portraits of you, based robustly on existing artist’s styles.

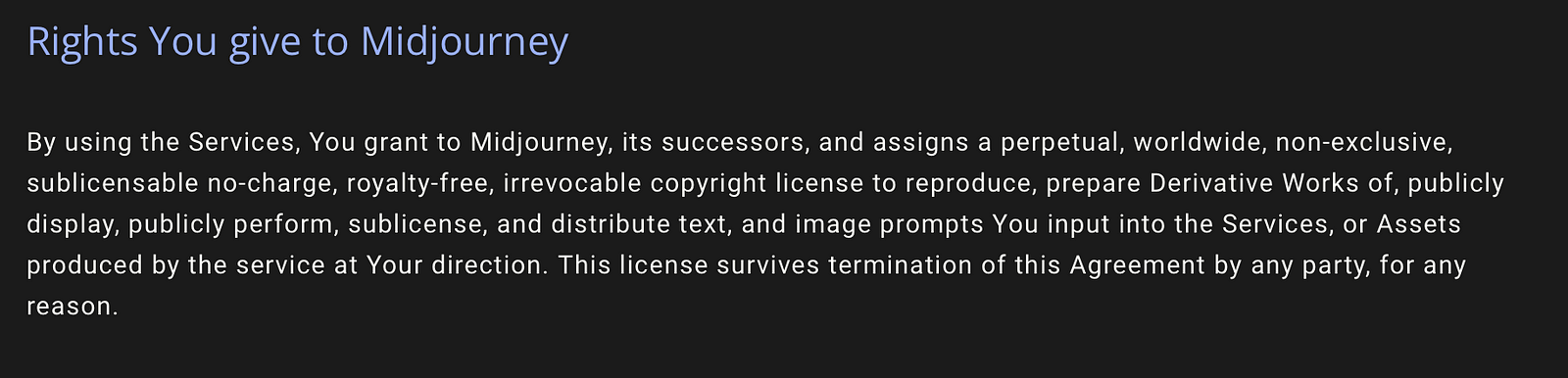

So platforms have been making up their own rules, since there’s no umbrella policy to cover things. Midjourney’s looks like this:

- people on their PAID MJ plan theoretically have copyright granted in anything they make, since it assumed the fact that they’re paying means they have commercial interests or incentives in using the programme; at the same time, an unlimited licence to use the image is granted back to the platform itself, meaning ‘it’ can do anything with it:

- Anyone else is free to put in exactly the same prompts used by someone else —you’d get a different output anyway, because that’s what ‘generative’ means.

- people on the FREE MJ plan (who it is assumed are generating experimentally or just ‘having fun’) do NOT get granted copyright:

Unusually, the UK is one of only a handful of nations to offer copyright for works generated solely by a computer, but it deems ‘the author’ to be “the person by whom the arrangements necessary for the creation of the work are undertaken.” Interpret that as you will.

In the US, there is currently no copyright protection for works generated solely by a machine.

It’s the chain of creation of an AI artwork that makes it so difficult to determine where the work ‘originates’.

AI-produced works of art start with a programmer (or more often, a large team of programmers) who have written an algorithm. That person may — or may not — provide some input data. Another person - an artist, or group of people - might do this. The output is then generated by AI independently.

So if an AI-generated artwork isn’t copyright-protected by law, anyone can freely make copies of, distribute it, use for commercial purposes or sell the work to anyone else; it can also be remixed, chopped, imitated, and so on.

…which sounds exactly like what can and does happen to copyright-protected work, just without the financial or legal consequences.

Which makes me wonder; the rather cruelly-named ‘prompt monkeys’ describing themselves as artists and selling their output online — don’t they want some ownership over what they’ve made? If Maureen’s keeping herself in fancy earrings through her Etsy shop selling those meaty He-Men, would she be mad if Dolly in Pennsylvania started ‘borrowing‘ her screen-shotted He-men, but to fund her Louis Vuitton habit instead?

Possibly not. Maybe that’s going to be the big pivot — that all art becomes universally, omnipotently open-source; no-one’s, and everyone’s property. There’s something in that I like the notion of, in an incredibly idealistic woo-woo kind of way — but then, money. Paying the bills, buying food, you know; the things we do to stay alive. If we already lived in a world where the Universal Basic Income was a well-established fact of life, and capitalism wasn’t the system, something like that could be beautiful.

At least one Midjourney user has it all figured out:

“Watching Artists get mad 😡 at ai wondering why? I mean as an artist I don’t understand copy rights [sic] because I’m constantly wondering about influences and I think these artists concerned with ai copying their art is a compliment because you know every artist is copying someone else’s work to inspire themselves regardless original ideas are very slim compared to imagination. As an artist I’ve never seen a non influenced art piece besides imaginary creatures and they’re [sic] not many left to create… never see any landscape artists bitchhing [sic] about the same mountain scenery…”

(I’ll wait a sec while you spot the really special bit.)

This is why there are big moves to work it all out, before the alleged robopocalypse — known in scientific terms as AI Singularity — hits. And my chat with Andrea very much started out as a list of questions about copyright, but ended up a broader conversation about the philosophy of art, its purpose, the human intention, and much more besides. He talked extensively about which artificial intelligence projects are already redundant — the self-driving car was an example—and which aren’t, such as medical and scientific problem-solving applications. There are things that are un-AI-able too — something it’s easy to overlook when there’s a constant stream of doomy prophesies flying at your head.

By the end of it, I felt reassured and freshly curious about AI and its place in our lives in a bigger-picture way. This was a man who works with the machinery on a daily basis - his life’s work — and if he wasn’t afraid, why should I be?

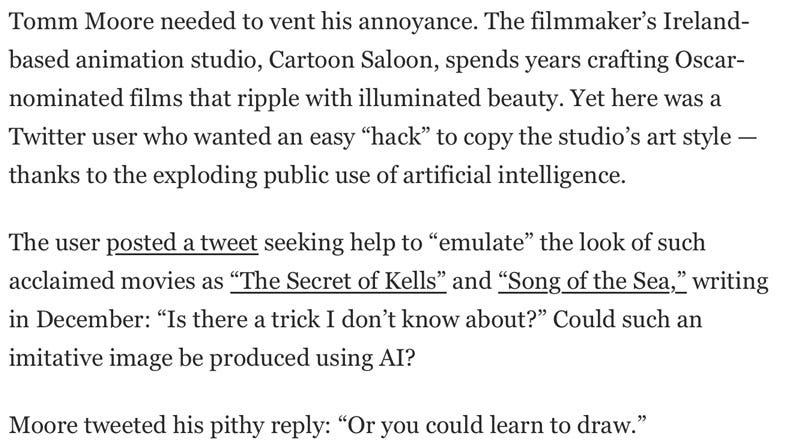

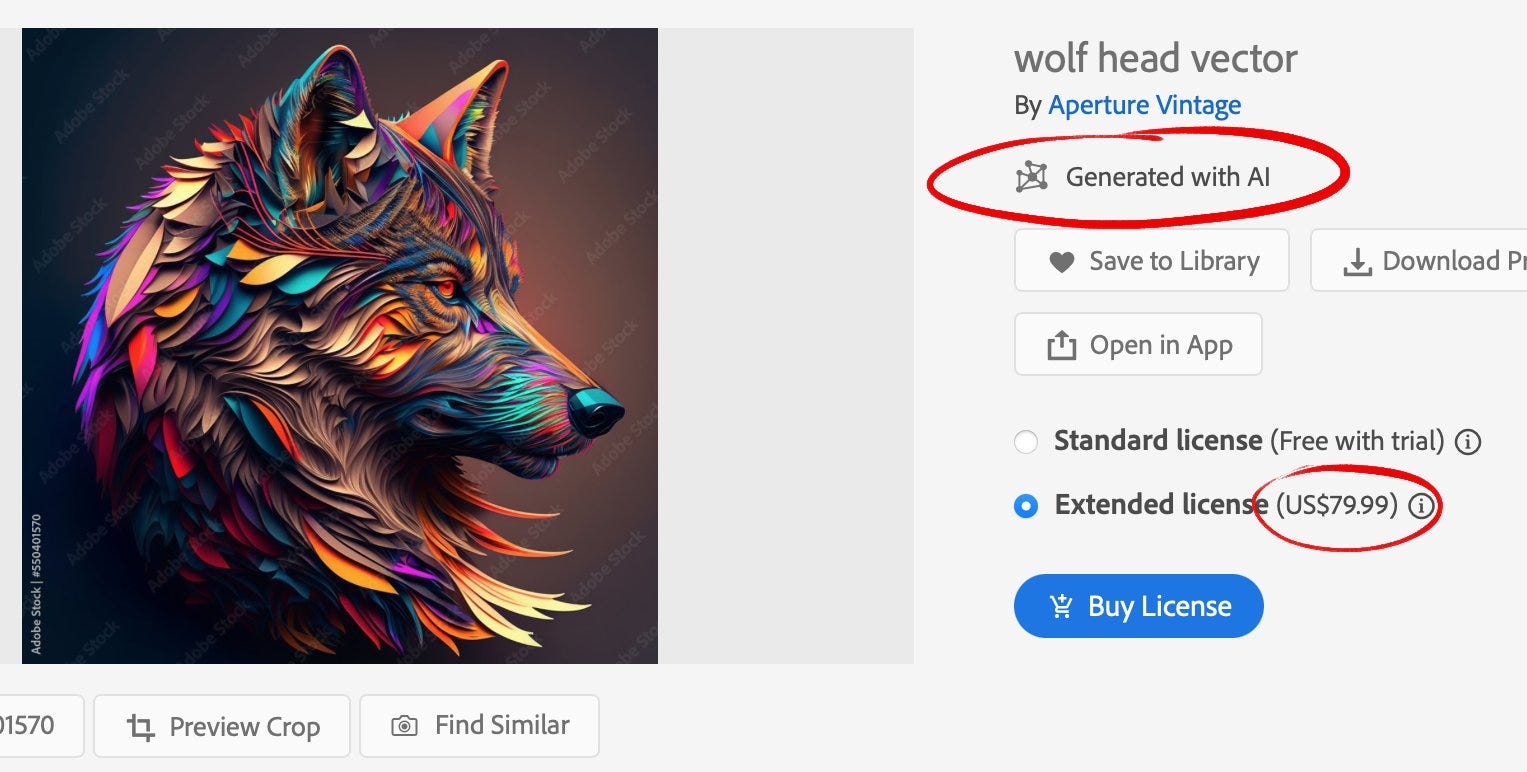

But there’s still the fact that copyright and ownership of intellectual property is tied up with money; it’s how revenue is generated for artists, through royalties, licensing, re-licensing, adding work to stock libraries and more. And since copyright is granted for 50 years after a creator's death, the artist is not the only human to benefit financially from their life’s work — providing wills are left and all in good order, children, spouses and grandchildren can, too. This notion of artwork being stolen by AI and melted into an enormo-bowl of cake mixture from which billions of new cupcakes emerge doesn’t simply put the much-maligned Tarquin The Painter’s nose out of joint — it could have a tangible, terrible impact on the futures of his dependants and descendants, too.

“Legislators will take forever to even fathom the tech, let alone build in any guardrails, so it takes things like litigation and public debate to move the needle on the ethical use of this technology.” — Jason Chatfield, president of the National Cartoonists Society.

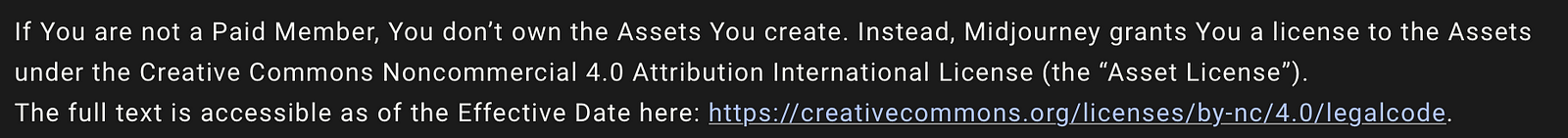

Hollie Mengert is an illustrator for Disney who found that her work was being cloned as an AI experiment by a mechanical engineering student in Canada. The student downloaded 32 of her pieces and trained a machine learning model that could reproduce her style — it only took a handful of hours. As she told technologist Andy Baio, who reported on the case:

“For me, personally, it feels like someone’s taking work that I’ve done, you know, things that I’ve learned — I’ve been a working artist since I graduated art school in 2011 — and is using it to create art that that [sic] I didn’t consent to and didn’t give permission for.”

“I see people on both sides of this extremely confident in their positions, but the reality is nobody knows,” said Baio in an interview with The Verge. “And anyone who says they know confidently how this will play out in court is wrong.”

For now, our own government has decided with the input of the Designers and Artists Copyright Society to scrap controversial plans granting artificial intelligence platforms an all-encompassing exception to copyright, asking instead to work with creative industry leaders to strike a balance between promoting innovation within AI, and supporting creativity in the UK:

“The debate followed months of objection by the copyright and creative industries warning of the detrimental impact the proposals could have on UK creators.”

The words ‘could have’, written in February, already sit uneasily with me having watched colleagues talk openly about reductions in their client work on social media; others new to the industry talk in bewildered terms about a tentative career they’ve just got off the ground that’s already impacted. Others at the very outset of their career, perhaps still studying or recently graduated, are openly questioning the point of pursuing such a career — careers that, as of 2020, were contributing almost £13million to the UK economy every hour.

— — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — —

I doubt this is the last time I’ll write about AI, though to be frank it’s been exhausting, keeping up, reading and archiving articles and continuing to walk the tightrope between my natural excitement and curiosity, and outright fear.

Though I didn't react the same way, I feel for the very, very established and much-loved Dave McKean, whose response to playing with AI for the first time was visceral:

“I spent a day on the floor of my studio in a foetal position…My immediate response was: Well, that’s my career over. Why would anyone pay me to do an album cover when anyone can type a few words into Midjourney and, in a couple of minutes, start downloading endless finished possibilities for free?”

I thought about ending this article by summarising the idea of AI itself as a playful, obliging but not very bright puppy that’s been let into the park too early, and everyone wants to play with it but as a result lot of people are getting bitten and shat on — but that sounds a bit naïve, and not quite right.

“There are a lot of people whose argument seems to be: ‘Well, the technology is here now, there’s no taking it back.’ I personally find that ridiculous because you’re just telling artists to give up without a fight.” — Sarah Anderson

Instead I’ll quote my partner Leigh:

Making AI Art vs Making Human Art is like masturbation vs actual sex with another person. It’s like PornHub; you go in and type what you want (‘big boobs’, ‘forties’) and there it is. You might get the same outcome, but none of the feels, the textures, the scents, emotions; you feel your way through.

Like a PornHub user, a prompter is always still sat safely tapping a keyboard. It has its place.

But an artist is in a way more akin to a porn actor; willing to go the whole way, in person, for real, many times over, to get the result they want.

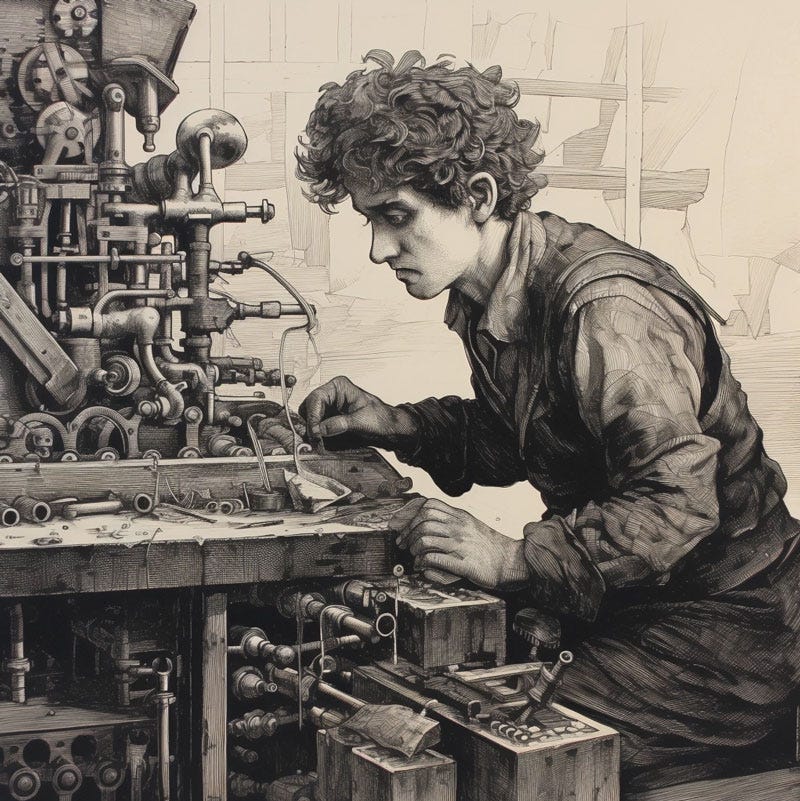

For now, I’m still refusing to think of AI (as it relates to art) as a monster that’s escaped from under the bed. I enjoy playing with it. I still think it’ll be useful to me and I watch in awe as people use the machinery to generate beautiful, beautiful things. The following pictures made me gasp, and almost brought a tear to my eyeballs — and if that’s not an example of a picture triggering a human emotion, howsoever created, what is?

Further reading:

https://www.mybff.com/discover/the-risks-benefits-and-ethics-of-artificial-intelligence

https://theaoi.com/campaigning/campaigns/consultations-blocks-2/artificial-intelligence/

https://theaoi.com/2022/12/09/artificial-intelligence-ai-aoi-survey-results/

Maybe this will interest you:

https://theaoi.com/event/aoi-webinar-ai-and-illustration/

PS: At the time of writing, AI is still struggling with type.

But the spectre of Banksy’s chimps is never far away.