This article’s been a long time in the making.

Not being able to ‘get to it’ has hassled me for ages but, as I finally get my assorted notes and thoughts assembled, I realise that quite unintentionally, the right time is now.

I’m writing about AI. Of course I am. Not only am I expected to have an opinion on it, as an artist (I do), but every man and his hamster knows about AI and moreover, also has an opinion on it. This is no bad thing; but you know that something’s ‘made it’ into the public consciousness when you’re asked to talk about it live on local radio; literally ‘the man in the street’ invited to share their thoughts on the matter, before switching to Sarah on the mic.

But more on that later.

In 2015 I began to play with Google’s DeepDream. Our mate Kev told us about it. You had to input a picture and wait for it to render — a long enough wait that you could go away and do something else, like have dinner and sleep, as opposed to Midjourney’s amphetamine-rush of fired-out images made in moments. In fact, facebook tells me I uploaded it on 30th July, and got the result on 2nd August:

So this was my first AI picture, and it’s a horrifying belter:

We laughed and pulled faces at it and then I forgot about it, and about AI for the most part other than following a few scientists on tumblr who were doing silly and very funny things with neural networks; getting them to write recipes, for example (generating the bewilderingly unappetising meal equivalent of what you see above) and poems. I would chortle at their painfully awful but nearly-there attempts, helplessly projecting human concepts like ‘trying really hard’ onto what I knew was not an earnest seven year old, but early machine learning.

A bit later I got to try out Adobe’s Neural Filters in a new PS update. I shoved a picture of my face into it and played with the sliders that deployed artificial intelligence to change expressions and age. The results were deliberately awful, because I knew I would never actually use them, so I went to extremes and pinged them off to family for Whatsapp LOLs. Regardless; the very gentlest of alarm bells was ringing. If I can change a face to this extent so easily, what’s to stop someone else changing a face for nefarious purposes?

Fast forward to 2022. Our mate Kev Again — featured previously after his mauling by DeepDream — mentioned an AI programme he’d been using to create pictures. He was having rather a lot of fun with it, and I had a go myself. Hm, I thought, yeah, it’s quite fun! (“Pin all the things”.) But I couldn’t really see how I might use it in my work, even if I’d wanted to, and besides, my contracts for client work are pretty much 85% a giant sign held aloft that says Thou Shalt Not Submit Any Work That Might Ever Have Had Anything To Do With Anyone Else Ever.

So, NightCafé Studio was also just a toy, then, and I forgot about that as well. Besides, at that very moment we were too busy getting excited about NFTs to think about artificial intelligence (more on THAT later, too).

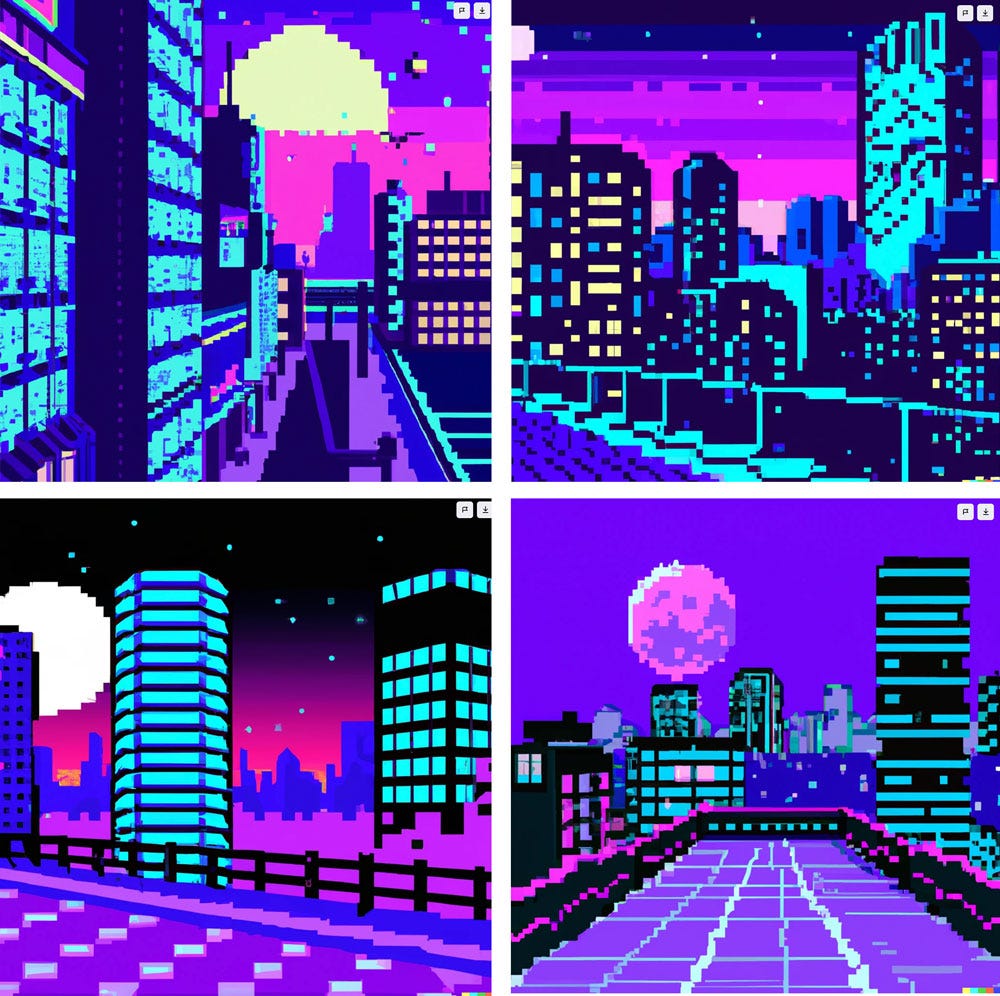

And then; out of the blue I got an invite to beta test an app called DALL*E, which made artificially generated pictures. As you might be able to tell by now, I’m never one to back away from the thrill of a new piece of kit or technology, especially one so apparently BRAND new that it isn’t even out yet, so I seized the day. I asked it rather predictably at first to make a picture of ‘a night-time street scene in an 8bit art style’, because I was deep into my vaporwave playlists that week. And it did. Not bad, so long as you don’t want to print it at any sort of acceptable resolution or pass it off as your best work:

I did it again; this time, ‘shopping for pens and ink in a haunted pen shop in the style of Aubrey Beardsley’. Hm; it made a decent fist of that too. In fact, I liked them quite a lot. They had a certain charm.

After a great deal of messing about, I realised I should really have a look at whether it could reproduce anything that looked ‘like me’ — I don’t mean ‘a portrait’, though that’s happened since (it didn’t work very well). I wanted to know if the system could produce work that looked like mine. For the first time, I got the barest inkling — pun entirely inktentional - of the theory of a notion of an idea of a suspicion that this might, at some point, perhaps be a threat.

Let’s go in with possibly THE most widely-known of my pieces of work, I thought. Let’s ask it for a cover for To Kill A Mockingbird. I could see from the results exactly what it had been trained on — I could even name some of the illustrators — but nothing was usable beyond rough concept sketches or layouts, with useless lettering.

I then asked for ink drawings of Christmas iconography — I thought I’d try some old and very mainstream work that’s been out there a long time. And it made some alarmingly naturalistic looking stuff. Immediately I was put in mind of all the times I’d been ripped off in the very early days of doing hand-lettering, by people and companies who should know better but were seeing hand-drawn type for the first time (we’re talking late 90s and early 00s) and weren’t thinking that lettering was capable of being plagiarised as well as images.

Despite the minor shudder, I kept on. I asked it to make words with ink. Totally illegible, though the energy was kind of there. Then logos. Then ink bottles. The cross hatching. Then illustrations for horror stories for kids…in black and white. Then landscapes in ink. And on it went.

It did them all, with its only stumbling block being that lettering was entirely unusable and hands were snigger-at-the-screen terrible. This was still only about a year ago, but even at that point a tiny but chilling voice was whispering Banksy’s ‘Laugh Now’ into my brain.

Over the course of the rest of the year I kept on playing. Kev Again was integrating AI into his image-making, and nicely so. Hands continued to be grim. But humans in my creative orbit began to make uneasy noises. I love tech, especially the sort that enriches my work and my process — whether the ancient Adana, my 80s Gocco printers or the latest Adobe feature, and I’ll be damned if I’ll be threatened by any of it; try it, learn it, and find out how I can deploy it. Another thing in the pencil case. But…but.

Never mind. On with the work. As well as playing with AI I was simultaneously immersing myself in the Web3 world, buying crypto, building an NFT collection and spending sometimes too much time in Discord because such things, just like Apple Pencils, Photoshop and magical things before them, are always just the next step in how we make, share and sell things. Nothing phased me — peak excitement was reached when minting a hotly-anticipated NFT after getting a whitelist spot. WAGMI! It was later stolen, but…yep, more on that later.

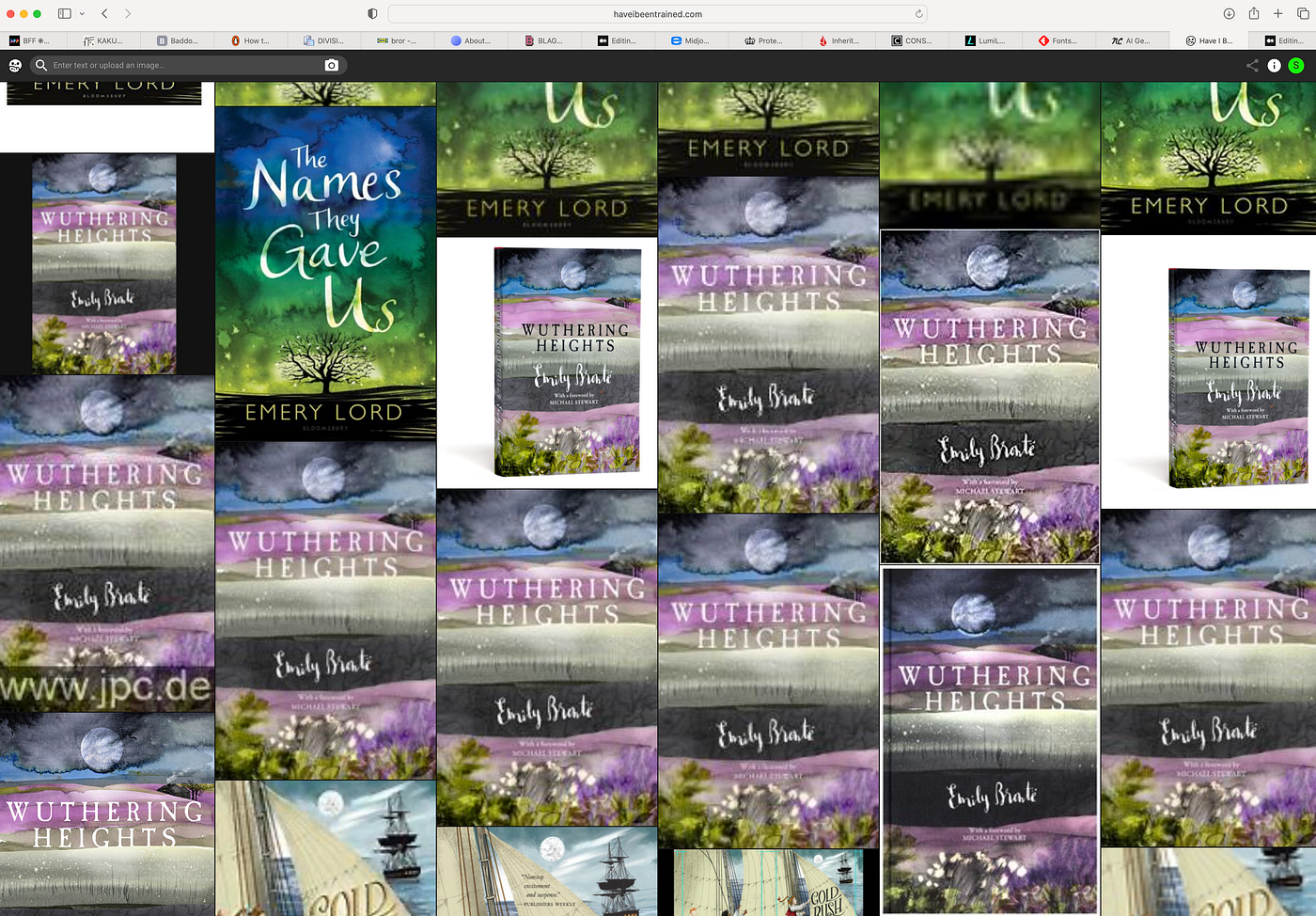

Around summertime I dove into Holly Herndon’s Spawning project. A lifelong lover of electronic sounds, I knew her records and was enthralled by her conjoined-twin Ai+Holly progeny. At the same time, she and her colleagues had developed Have I Been Trained?, a site which claims to allow artists to choose whether or not their images can be scraped for use by Stable Diffusion, MJ and OpenAi. I thought long and hard about what to click, yes or no. Did I want my images included in any large image training model? In what feels like a lifetime ago, I had a rather generalised feeling at the time that I didn’t want to be *excluded* from the world of AI, so clicked ‘Yes’. But that wasn’t actually what was being asked, and by the time I understood the specifics of the question some time later and went back to change it to a ‘No’, the site had inverted its system to one where, rather than choosing to opt in or out, you had to manually seek out any images of yours in the system, and ask for them to be excluded one by one (that’s still the system they’re using today).

I carried on. Towards the end of the year the world of commissioned work began to feel distinctly odd, with subtle but long-in-the-making shifts in modus operandi, their origins in the pandemic, finally manifesting in the way that work was coming in (awkwardly, unpredictably) and being managed (slowly and painfully). I began to see colleagues talk publicly about work being ‘weird’, and turnover being down. Against this landscape, my social media feeds began to fill up with people excitedly spewing out picture after picture made mainly in Midjourney, some calling themselves…artists. I, businesslike as ever, shut down the usual quarterly roundup of IP violations on Redbubble and Etsy, annoyed by the usual brazen help-yourself attitudes to artists’ work in the public domain — something which feels quaint now — and continued to stay abreast of the NFT world despite a sobering wallet theft, a gifted NFT stuck in cyberspace and a shady ‘buy it back’ deal with an anonymous stranger.

In the run up to Christmas I was busy with the annual seasonal promotion, the demands of the daily Inkvent project and assorted client jobs. I didn’t ‘play’ with AI again until the new year, using it to generate some atmospheric 80s-style pieces as refs to try and capture the vibe of some upcoming illustration work, and to experiment with layouts for a looming book project. We used MJ to make targets for my Dad’s shooting practice — zombies who may or may not look like certain politicians, all OK because of course they weren’t real people — and introduced my Mum to AI, whose first Midjourney piece was a beautiful Japan-inspired coastal landscape rendered in ‘ink’. She was fascinated, and loved the process — “I can put away my paints now’”, she said. “So can I”, I said, trying not to let inherited gallows humour extinguish her lovely anticipation.

I made a part-AI-part-Photoshop-part-Procreate leaving card for a mate, and used it to help make a silly birthday card for my sister. It was useful for generating some demographically accurate reference figures for an artwork I was making. And I did some more of those 80s experiments. I even started an Instagram page to capture the best ones. Kev Again continued to deploy AI subtly and successfully in his design work, and although I still hadn’t found where AI might ‘fit’ into my work, I still felt like it was a friend rather than a foe.

And then…and then. I joined the Midjourney facebook page, and at the same time, people calling themselves ‘professional prompters’ (to a great deal of derision and hilarity) and ‘AI artists’ began writing about how ‘real artists’ had somehow been gatekeeping, hiding secrets and lying about how long it took to create work. Look! many of them said; it IS easy after all! How dare those artists charge so much to do this!

Almost overnight, the world seemed flooded with articles about AI: the threats, the warnings, rabid defence of it, declarative statements against, over-confident opinions thrown in all directions. People fought to defend their use of AI, to explain why human artists didn’t deserve to keep working, and others outlined how the world could never be without human-made objects and pictures. My stateside agency had begun to talk about it in their newsreels, and my Medium feed was suddenly full of tediously repetitive articles loudly telling me how to generate five-figure sums with a ChatGPT side-hustle. How to generate pictures in Midjourney and flog them back to people via Adobe Stock. How to bypass concerns about copyright to make AI pictures to print and sell on Etsy…oh, yeah, Etsy. Back to that old chestnut.

I talked about AI at length with my agency’s boss, collected opinions and followed real-world artists creating beautiful work using AI as one of their tools, trying to keep healthy, future-positive role models in my line of sight. I remained determined to be neither for nor against AI, neither scared nor cultishly absorbed by it. And despite wanting to pontificate in the public domain many times, I held off writing about it, not wanting to add another voice to the clattering hubris of prompters calling themselves artists, and artists throwing shade on users; the world did not need another article wanting to sound knowledgable and finite.

So I didn’t, until a single tweet brought me to the BBC’s attention.

Chapter 2, in which I talk about my research with regard to AI + copyright + IP, follows.